Crafting a visual arts-based educational experience for your learners takes a bit of planning. Whether you’re considering an evening at the museum for your healthcare team or creating an entire humanities curriculum for your institution, this section will guide you through common considerations to optimize your learners’ experience. For more specific guidance, visit our course materials resources and artwork repository.

For more information about arts-based education, see The Fundamental Role of Arts and Humanities in Medical Education | AAMC and The Integration of the Humanities and Arts with Sciences Engineering and Medicine in Higher Education | National Academies.

For training resources, see the Art Museum-based Health Professions Education Fellowship at the Harvard Macy Institute and the Visual Thinking Strategies nonprofit.

Brainstorm your goals

The first questions to ask are who is your target audience and what are their needs? Experiences have been designed for undergraduates, medical students, and interprofessional teams, among others. Either you can perform a needs assessment of your learners to assess their learning goals or you can decide on which clinical skills to emphasize with your intervention based on your own assessment of learners’ needs. For example, many medical school experiences emphasize observation skills with the goal of sharpening students’ diagnostic acumen. Other goals may include focusing on self-reflection and metacognition, finding joy in practice, building empathy and tolerance for ambiguity, and learning to work as an interprofessional team. All these goals can be incorporated in experiences geared towards at any stage of learner.

You can find examples of coursework at Emory on this site, and examples of syllabi from other institutions at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Contact a museum educator

After you have an idea of what you hope to achieve, we recommend contacting a museum educator at your local art museum. Museum educators are trained professionals who share knowledge about objects and exhibitions at museums. Given their expertise in teaching, we recommend that you develop a partnership with your local museum educator and co-facilitate experiences with your learners. If you are located in the Atlanta area, feel free to reach out to Elizabeth Horner at the Michael C. Carlos Museum to get started. Teaching resources at the Carlos (including admission and consultation with museum educators) are freely available for Emory faculty and students.

If you do not have access to a gallery or museum in your area, you can curate an experience using preselected images. Please see the “adapt for online teaching” section for more details.

Choose an exercise

We use art as “third things” to foster deep discussion on a variety of topics pertinent to healthcare (1). More specifically, the third thing is an object that displaces emotions and cognitions so learners can access complex emotional thoughts and even “taboo” topics through a work of art. We will provide examples below to show the power of the third thing in healthcare education through introducing three exercises: visual thinking strategies, the personal response tour, and back-to-back drawing. For more detailed exercise materials, please visit the exercise resource pages linked below.

Visual thinking strategies

While there is no one way to do arts-based teaching, most experiences use a form of pedagogy called Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS). In a VTS session, a facilitator works with a group of learners to discuss and interpret an image – in our case a work of art.

Personal responses tour

The personal responses tour uses art as a “reflective trigger” to “promote individual reflection, foster empathy, increase appreciation for the psychosocial context of patient experience, and create a safe haven for learners to deepen their relationships with one another” (2). Learners are given a prompt design to evoke an emotional response and connection to a work of art.

[LEARN MORE ABOUT PERSONAL RESPONSES TOURS]

Back-to-back drawing

In this exercise, learners work on listening and observation skills, interpersonal communication, and dealing with uncertainty. Learners sit back-to-back with one learner describing a work of art in words while the other learner interprets and draws what they hear. This exercise can be done with a group watching the process and taking notes on what is said and what is drawn. It can also be done without a group watching. We often do this exercise with a group watching a dyad after which pairs break off and select a work of art for the exercise. We often use this exercise in the setting of a longer course as a more fun activity to highlight the art of communication, especially if the other exercises involve heavier and more metacognitive processes.

Pick a theme

When selecting artwork for an arts-based experience, we recommend that you choose a theme or two to ground and focus your discussions about a work or collection of art. For example, your may choose to discuss mental illness, stigma, death and dying, implicit and explicit biases, empathy, or the doctor-patient relationship (2). This is a separate objective than identifying a learning goal; for example, you may have a learning goal of increasing tolerance for ambiguity (i.e., tolerance for not finding “the right answer” when presented with complexity). To address this learning goal, you may choose to focus your theme on death and dying (for example, “Patient” by Frank Moore can be used to discuss death, loss, transience, and healthcare, among other themes) or interpersonal violence, war, and racism. In our experience, once we feel the group is comfortable working together and has practiced viewing and discussing art using the VTS method, we then push learners to broach more personal and introspective topics like personal identity, challenges empathizing with the pain and suffering of others, and approaching interpersonal conflict.

We have designed a variety of courses by choosing combinations of the following themes: joy, pain, suffering, empathy, identity, connection (teamwork), and seeing (learning to see). Please see resources

For example, we have used the works of art below with a interprofessional palliative care cohort to discuss how we feel when caring for people whose values we do not share and the challenges of bearing witness to pain, suffering, and violence:

The Jubilant Martyrs of Obsolescence and Ruin, Kara Walker, 2015

Hale Woodruff, The Mutiny on the Amistad, 1938

Get institutional buy-in

We recommend that you have a clear objective(s) about your proposed arts-based experience when speaking to your institutional leadership. Consult with your curriculum committee or program leadership about the best mechanism for introducing new elements to your learner population.

Likewise, we recommend that you have the support of your institution when seeking to create a partnership with your local art gallery or museum. Importantly, we recommend that your institution be able to provide protected time for your learners during their experience, whether it is looking at images from inside the hospital or viewing works of art in a museum. No learner should be expected to take clinically related phone calls while engaged in this work. We find that our learners prefer going to the museum over remaining in a healthcare setting to discuss works of art. Placing physical distance from learners’ place of work allows them to fully immerse themselves in the art and museum experience. Furthermore, it allows members of the team to get to know each other away from the typical social structure and clinical hierarchy of a healthcare system.

Put it all together

We recommend that all arts-based educational sessions include an introduction to the goals of the session, clear disclosure of ground rules for conduct, and a wrap up/debrief prior to finishing the experience.

Introduction

We ask that learners present 15 minutes prior to the start of the session to allow them to settle in and adjust to a new learning environment. We gather in a circle, generally outside of the museum galleries (for example, in the lobby or atrium), and begin the session with meditation, a reading, and discussion about the learning objectives and topics to be discussed. Our learners find that priming them with the learning objectives and themes primes them for the exercises using art. For example, if the theme of the day is empathy, we may begin by asking the group: tell us about a situation when it was challenging to connect or empathize with a patient? What was challenging about it?

Groundrules

Prior to going to the galleries, we disclose the ground rules for conduct to ensure that all learners are treated with respect and to create conditions conducive to reflection:

- Confidentiality is maintained in group

- Stay within your comfort zone with respect to revealing personal information and feelings

- Group members should not question or challenge the personal responses of others

- No phones* (except under special circumstances)

- Avoid concluding what the piece is about or figuring out the “right answer”

- Try to avoid artists’ names, intent, style, periods, art history jargon

- Do not interrupt others’ thought process (let one person speak at a time)

- Focus on the questions that we ask you.

Arts-based Exercises

While in the galleries, depending on the goal of the activity, we often have learners bring pencil and paper (depending on the gallery or museum’s rules) so learners can draw or write while reflecting on a work of art. We generally allocate between 15-30 minutes for each activity, as detailed in this paper (4). In the image below, medical students enrolled in an elective on art and surgery sketch to practice their observation skills.

Wrap up/debrief

To conclude each session, we gather again in a circle to reflect on the activities and tying what we experienced in the galleries with our clinical practice. To revisit the example of the class centered around the theme of empathy, our learners worked on naming implicit/explicit biases and barriers to empathy both individually and as a group using VTS and personal responses tour exercises. They also spent time alone with a triggering work of art to work on strategies to connect with the work of art and also named their cognitive and emotional processes to show empathy for something they did not like. In our debrief, our facilitators asked: how is the process of trying to empathize with a challenging work of art similar to empathizing with a patient or family whom you find challenging? How is it different? What tools can we use from today to bring back to the clinic?

Run a successful session

Over the years, we have come across challenges when planning for our arts-based experiences. Here we share some advice to give you the highest chance of success:

1) Do a walk through or two in the art galleries with all the facilitators prior to your session. We go to the museum prior to each class to make sure that our selected artwork is appropriate for the session’s goals, to practice facilitating, and to make sure that our clinician facilitators and museum educators are all prepared for the upcoming class.

2) Try to get funding for learners to have an annual museum membership. Our learners who get annual museum memberships as part of our courses often gather outside of class for special events such as jazz nights or just to look at art with their friends, family, and colleagues. We find that this kind of gathering helps form community and helps reinforce lessons learned during our classes.

3) Make sure you figure out parking. Parking in museums can be expensive so make sure that you have funding to allow for parking to be reimbursed. Encourage carpooling.

4) Ensure that your learners do not have any clinical responsibilities during the sessions. Having a learner get paged during class is not conducive to a productive learning session. Make extra sure that learners and facilitators will not have any clinical distractions during class.

5) Meet with your facilitator group after each session. It’s important for facilitators to debrief after each session. What went well? What could have been better? We find this debrief to be invaluable to improving the quality of each subsequent session.

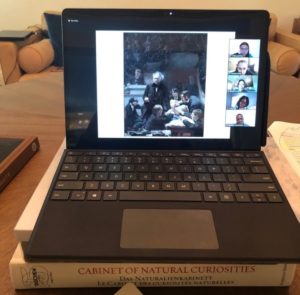

Adapt for online teaching

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to adapt our courses to an online format to maintain social distancing. We displayed images and engaged in discussion over Zoom. For personal responses tours, we used curated collections of images for learners to browse instead of walking through art galleries. While we found the rapid transition to online formats a success, our learners – by virtue of remaining in the hospital or clinic – sometimes turned off their videos write notes, take phone calls, and complete other clinical duties. In a focus group following a class that began in the museum and ended on Zoom, learners emphatically preferred meeting in person in the art museum.

Acknowledging that we prefer in person immersive experiences in art museums, if this is not possible then we recommend the following: 1) working with a museum educator to ensure high quality images to use over a teleconferencing platform, 2) ensuring that learners are not beholden to clinical responsibilities, and 3) requiring that all learners keep their videos on during the session. Please refer to the following articles that highlight online arts-based curricula (5-6).

When selecting artwork for an online session, or even an in person session using projected images, we found the website BEAM (Bedside Education in the Art of Medicine) to be highly useful to select images (7). Works of art are categorized by theme and include joy, meaning, loss, love, fear, and grief, among many others: https://beam.jh.edu/

Sources

(1) Gaufberg, Elizabeth, and Maren Batalden. “The third thing in medical education.” The Clinical Teacher 4.2 (2007): 78-81.

(2) Gaufberg, Elizabeth, and Ray Williams. “Reflection in a museum setting: the personal responses tour.” Journal of Graduate Medical Education 3.4 (2011): 546-549.

(3) Chisolm, Margaret S., Margot Kelly-Hedrick, and Scott M. Wright. “How Visual Arts–Based Education Can Promote Clinical Excellence.” Academic Medicine 96.8 (2021): 1100-1104.

(4) Chisolm, Margaret, et al. “Transformative Learning in the Art Museum: A Methods Review.” Family medicine 52.10 (2020): 736-740.

(5) Kelly-Hedrick, Margot, et al. “The Online Art Museum.” MedEdPublish 1 (2020).

(6) Stouffer, Kaitlin, et al. “The Role of Online Arts and Humanities in Medical Student Education: Mixed Methods Study of Feasibility and Perceived Impact of a 1-Week Online Course.” JMIR medical education 7.3 (2021): e27923.

(7) Kim, Kain. “Bedside education in the art of medicine (BEAM): A learner’s perspective on arts‐based teaching.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice (2021).